Before you start looking for a literary agent, you need to have written a book. And it shouldn’t be a first draft. You need to have a polished draft of your manuscript that’s ready for publication. This isn’t a rule or anything, but when you consider how many authors you’re competing with, it makes sense that you’d want to put your best foot forward. Now, if you’re one of the lucky few authors who finds a literary agent to represent you, then what they do is shop your manuscript around to publishing houses, usually starting with the Big Five. If your agent has enough clout, they’ll be able to get your work looked at right away. Otherwise, you may have to wait a few weeks—possibly months—before you get accepted or rejected.

Even if the Big Five all reject your work, there are still plenty of small publishing houses throughout the country that your agent can shop your book around to. If you’re lucky, the agent will eventually place your book with a publisher, securing you a publishing deal in the process. Their cut of the deal is usually about 15% of whatever you're making, so you can rest assured that they’re going to negotiate for as much money as they can get you. After the deal is complete, you’ll generally see your book published about two years later.

So, that’s traditional publishing.

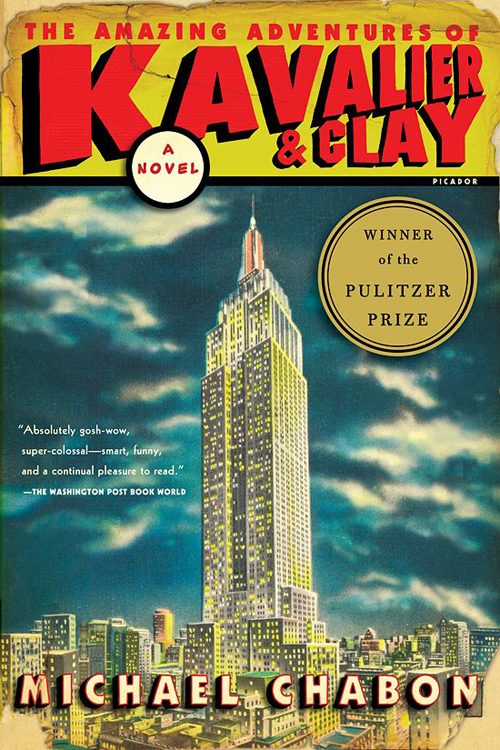

In 2004, I decided to write my first novel. This wasn’t decision I made lightly, either. I knew that writing a good novel would take time and effort, so I wanted to make sure I was ready for it. I was about halfway through writing that novel, when I met a literary agent in person—in the flesh. For an aspiring author, this was akin to meeting Santa Claus. I was at the Squaw Valley Community of Writers, which is a terrific conference held annually up near Lake Tahoe. Several amazing writers have passed through Squaw Valley on their way to becoming professional authors, including Amy Tan, Michael Chabon, and Janet Fitch. My pal James Brown also passed through Squaw Valley on his way to becoming a novelist and, later in his career, a memoirist (he’s actually the one who told me about Squaw Valley and encouraged me to apply).

In 2005, I was lucky enough to have been invited as a participant. In order to get invited, you send in a sample of your writing—either a short story or a chapter from a book. There is no application. If they like your writing, they invite you. If not, they don’t. Spots are limited. The first time I applied, I was put on the waiting list, but didn’t get in. The next year, I decided not to try—wounded ego and all. The year after that I applied again, this time successfully. My primary goal in attending Squaw Valley was to meet an agent who would want to represent me. Had I know what an amazing experience my week there would be, I wouldn’t have cared at all about meeting an agent. But, at that point in my journey, all I cared about was getting published, so meeting an agent was paramount.

Anyway, I did meet an agent and he liked my potential. He asked if I was working on anything, meaning a book. I told him I was writing my first novel and, after that, I went on to make perhaps the worst pitch in the history of pitches. But, I was nervous and he could tell I was nervous, so I think he gave me a pass on the terrible pitch. He told me that when the book was ready he’d love to read it, so to send it to him. He also told me to take my time. He stressed that part. Take your time.

Well, I didn’t listen. I was way too excited. I mean, an actual literary agent wanted to read my book—and I hadn’t even finished writing it yet! I didn't even have to send him a query letter! When I got home from Squaw Valley, I finished that novel as quickly as I could—which ended up being about three weeks. I sent it to the agent and about two months later I received my first rejection letter. It was heartbreaking, but I was determined to move forward. For the next several years, I made collecting rejection letters something of a hobby. I have a whole collection of them in a three-ring binder. And trust me when I tell you it’s filled.

I continued working on the novel, hoping that some polish would make it more attractive to agents. It didn’t. So, I eventually decided it was time to write a new novel. This was a terrifying prospect, because I’d already invested a couple of years writing and revising the first one. But, I knew that if I stood a chance, I’d have to write something more commercially attractive—at least, that's what I thought I had to do—so I began writing the novel that would become Inside the Outside.

When Inside the Outside was complete I began sending query letters to literary agents. Just as it was with my first book, Inside the Outside received a whole host of rejections. There was a heartening difference, however. Many of the rejections were personalized. When a literary agent takes the time to give you a personal rejection, it generally means they sort of liked your pitch. The norm is to receive a form letter, which you can all but be assured was mailed out by an intern or an assistant, while the agent probably never even saw your query letter. So, if the rejection is personalized, it means they did actually see your query and maybe even considered it. Because I was receiving a number of personalized rejections, I took this as a good sign, that it was only a matter of time before I found a literary agent.

After about a year and a half or so, I began to lose hope. Along the way, I had two close calls with agents who were interested in the book. First they asked for a partial, roughly the first fifty pages. After the partial, they each asked to see the full manuscript. Both agents ultimately rejected the book, but I was still sort of heartened because I’d never gotten that far in the process before. I took this to mean that I’d done something right and it was worth it for me to continue fighting to get Inside the Outside published.

But, soon enough, all the rejections began wearing down my confidence. I was sending out about three or four queries a week, off and on, for about two years and they were all coming back with rejections—that’s assuming there was a reply at all. Very often I never even got a rejection letter, which is arguably the worst type of rejection. I found myself at a crossroads and I needed to figure out my next move, which appeared to be self-publishing.

At this point, I was aware that self-publishing was generally looked down on in the publishing community. If you were self-publishing, naysayers generally believed that whatever it is you were publishing wasn't very good; the inherent logic being that if your work was good enough, you would've already been published traditional. Self-publishing was seen as the last resort for undesirable writers.

Suffice it to say, I didn’t want my work to be soiled by the stigma of self-publishing. But, if I continued getting rejected, I feared my novel would never get read by any readers. Anywhere. In the end, I decided that I'd rather engage my energy in a grassroots effort to publish my book and build an audience, rather than seeking the validation of the traditional publishing industry.

And that's what brought me to the doorstep of independent publishing.